Scientific materialism is the driving force of corporate capitalism and neocolonialism. Psychedelic political and spiritual culture stands opposed to this and by its nature is a challenge to this destructive ideology

Scientific materialism is the driving force of corporate capitalism and neocolonialism. Psychedelic political and spiritual culture stands opposed to this and by its nature is a challenge to this destructive ideology

Scientific materialism is the dominant philosophy of the modern age, and has been for over a century. The combination of science and technology as a tool, and capitalism and colonialism as the ideology driving its progress, has led to a widespread transformation of habitat and global indigenous communities. Alongside this essentially atheistic materialism, liberal secularism, originally a religiously motivated ideology that came out of the European Enlightenment, attempted to mitigate the destructive aspects of this transformation, but time and again has been cast aside, as corporate profit and nationalism remain a brutal mental and emotional driving force that has been effective in redirecting popular dissent at confrontation and crisis points, preserving the authority of establishment elites and institutions.

In the midst of these dominant ideologies, much progress has been made on a surface level, in saving and prolonging life, engineering fuel and communication pathways, journeying to other planets, a deeper understanding of the composition of the natural world, and deeper still into the very substance of matter.

Liberal secularism has also broken ties with church and state and allowed human autonomy in specific areas of life. But as ecological and social breakdown rises, and the limits of corporate capitalism are exposed, racism, sexism and bigotry have intensified. Psychological anxieties seem also to be on the increase, and extreme militant religious fundamentalism has become the focal resistance to corporate capitalism and materialism in its willingness to use violence as a reaction to the violence inherent in the system. The fundamental nature of being remains elusive for the materialists and the venom with which they attack competing ideological worldviews, particularly those of a religious or spiritual nature, is very likely to be psychologically connected to this frustration at the limits of physicalism to understand the nature of consciousness and a denial of the connection between reductionism and globalisation.

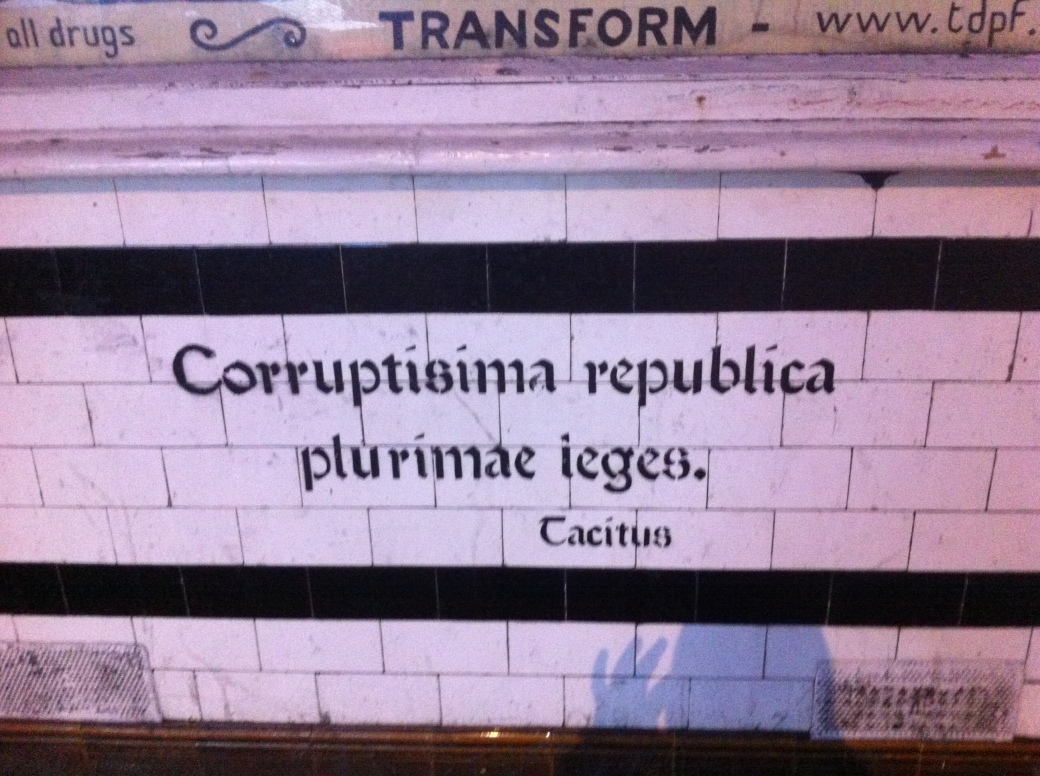

The development of psychedelics over the past 50 years offered a bridge between the physical and idealistic perception of reality, between science and religion itself, and it seemed for a time that ideas and philosophies were converging, and a political revolution was somehow linked to this, nowhere more evident than in the late-1960s and again in the late-1980s where alternative communities challenged the dominant modes of thought. But the political establishment, a mixture of traditional religious and atheistic worldviews, joined forces each time against a set of ideas that demonstrated nonconformist even revolutionary attitudes, threatening those who sought to retain control of the narrative, of the ultimate power to define reality. So laws were tightened, rebellious individuals and groups were militantly policed and imprisoned, and idealistic political resistance was attacked by all means deemed necessary.

But a new development began to take shape in the 1990s, as scientists consciously distanced themselves from the political elements connected to psychedelics and began to focus on neurochemistry and developing brain-imaging technology, which demonstrated the positive benefits of certain psychedelic substances to treat a variety of physical and psychological conditions causing distress in individuals. While alternative and more psychospiritual treatments continued, the dominant worldview found it much easier to accept this less political, more physicalist model, and the scientists focusing on this aspect seem to have become the spokespeople for the resurgence of psychedelics in the mainstream media with calls for medical licensing rather than an outright end to prohibition. Now it seems that the very notions of spirituality, religion, shamanism, even spiritual political views once intimately bound with psychedelic use, are being marginalised in favour of this sanitised, corporate friendly model of psychedelic health.

The risks with taking the reductionist, scientific approach is that at the very moment when a libertarian culture, with its open-hearted view of spirituality, sexuality and multiculturalism, is being attacked in quite vicious ways by the ascendancy of post-fascist ideology, psychedelic science is playing handmaiden to these forces by remaining apolitical and hoping these repressive forces will grant some licensing to allow the doctors to prescribe psychedelics as medical treatment, while researching the effects of these substances on brain chemistry. The possibility that these substances could provide the revolutionary perspective that might challenge the evidently repressive forces, perhaps even offer insight that might aid activists and campaigners in looking for alternative methods of challenging these tyrannical structures, is being pushed aside for a different kind of political expediency, one that is compliant to the forces of repression.

Can psychedelic, political and spiritual activists who want a complete end to prohibition find common ground with scientists and politicians? Can an integrated worldview to face the ecological and social challenges of the 21st century be created? Or is it time to recognise that legalisation of psychedelic substances will never be granted in this present system and to recognise the nature of the challenge and to find common cause with activists rather than government-approved scientists? The cognitive freedom to explore consciousness and create spontaneous recreational spaces, including non-materialist, non-rational, even post-factual perspectives, must be fearlessly expressed, not only in the face of the political establishment, but also the scientific establishment, and the reductionist ideology which has become prominent in the field of psychedelic research must be challenged. The transformation of the social and political order, which is visibly sinking into totalitarianism as it destroys the planet and any semblance of civilisation and humanity, no longer allows for politeness in these matters.

Dear Guilio – Knowing that we share similar concerns in regard to the subject matter of your blog, you might be surprised I’ve not thrown in my two-penny-worth sooner. It’s just that I’m struggling to keep up with all correspondence, etc, lately. You’ve written a challenging piece here and rather than call you out on parts of this piece that I might take issue with or query, I’d rather just say that I do share your concern that scientific authority is taking ownership of psychedelics. I talked briefly with Gyrus about this at the showing of the Sunshine Makers by the Psychedelic Society. In response to my concern Gyrus pointed out that there still is what I guess on might call a psychedelic underground, but that it doesn’t advertise itself on Facebook. I’m sure that’s true but how politicised is it? I guess its members are proponents of complete decriminalisation, but not a group that exercises radical political action. Certainly, having a shared nitrous oxide driven ‘Be-In’ outside Parliament just looks like a student prank.

I actually suspect that the fact that for a period of time LSD and other psychedelics catalysed a pre-existing culture of resistance to materialism, capitalism, consumerism and scientism and became a key point of reference for that culture of resistance in the media, was an accident of history rather than indicating that psychedelics necessarily radicalise their users politically or socially. Rather that an alternative culture found in psychedelics a useful technology of resistance as a rational disordering of all the senses proposed by Rimbaud in the nineteenth century. What I think characterises psychedelics is their power to disrupt normal processes of perception at every level, which does allow for a revaluation of existing prejudices, assumptions, etc, and powers their therapeutic potential. But this just does not guarantee that the outcome of psychedelic experience is a commitment to your favoured libertarian culture, with an open-hearted view of spirituality, sexuality and multiculturalism.

The scientifically orientated enthusiasts for psychedelics argue for a ‘softly, softly catchee monkey’ approach, claiming that proof of scientific and medical value will, or at least may lead to decriminalisation or at least some kind of licencing for adult personal non-medical use, which I very much doubt. I accept that there is a powerful Statist resistance to personal use of psychedelics, but not only on the basis proposed in the famous Terence McKenna quote, but simply because they powerfully disrupt normal processes of perception and are therefore essentially toxic agents that need to be regulated to protect the general public. All medicines are essentially toxic in that they interrupt normal bodily processes, even though in that process they also interrupt pathological processes at the same time. Albert Hofmann himself was prepared to state for the purpose of a British court that LSD was a poison, (see Andy Roberts’s ‘Albion Dreaming’), that is necessarily the scientific view. As someone put it ‘there is no effective medicine that does not have side effects’, in other words all medicines are poisons that have beneficial side effects.

Getting back to your blog – Sorry! You ask ‘Can psychedelic, political and spiritual activists who want a complete end to prohibition, find common ground with scientists and politicians?’ I doubt it, though at Breaking Convention at least they run in an alliance of assumed common interests. What the scientists are saying to Government is ‘please let us play with these substances; they do have therapeutic potential and offer scientific insights’. It’s a very long jump from there to saying ‘Please let us play with these substances; we enjoy disordering our senses because of the insights so derived or just because we find it a fascinating and generally pleasurable experience’

Thanks for the response. I agree with some of what you say, but wanted to offer some thoughts on where I’m not so sure. I agree with you that there is no automatic liberalisation of the mind that comes from use of psychedelics. As is well-documented, set and setting is of vital importance, cultural background noise is hugely influential and as you say can catalyse what is existing both in the individual and in society and in the time, which is why I particularly referenced (and how synchronicitous, perhaps “there are no accidents”) the 60s and 80s, both turbulent and transformative politically in Europe and the US and their sphere of influence. LSD and MDMA were both respectively central to the counterculture of each decade, and their respective countercultures in a very loose way were political, even if the politics were anarchic and transgressive often in a way that embraced difference, rather than focused on othering, as overly individualistic and rightwing thought often is. I of course take your points from your presentations about various subcultures who made different use of psychedelics, and I make no bones about presenting a subjective political view which is more in line with a kind of leftist spiritual view which is common enough and recorded in both acid and ecstasy counterculture. Such a politics I feel is still needed.

We could discuss and debate this at more length, but for now I would just like to add a couple more points on what I see as the creeping control of the narrative that I am noticing in the medicalisation of psychedelics. I have what I consider a healthy respect for science and the research being conducted, because it is repeatable and grounded, and has, up to a point, the respect of the existing power structures, even if they do fear that legalisation could lead to some moral degeneration in society. Theresa May who took the issue of drug prohibition back 10 years as Home Secretary openly talks about her Christian moral outlook, so it’s not hard to recognise a moral panic in her stonewalling of discussion on this issue. So I’m not sure in the light of the medical evidence of their relative safety, that toxicity is really anything to do with that panic.

But finally and this is my main problem with the medicalisation, it is imprinting an assumption that psychedelics have to be administered by an expert of some kind, a medical professional in the case of science and even in the predominance recently of ayahuasca, of a “shaman” or recognised healer. This is reinforcing authoritarian power structures, which seems to highlight the fear both in scientific and religious circles, of an individual having a leaderless transformative experience, or indeed one in a group of peers, as when young people go out clubbing and take their first “e”, still of course some hierarchy, but much looser and surely more of a modern rite of passage. While in some cases in terms of healing (in its broadest sense) this administering is right and proper, if the idea of recreational use which is in many senses the central element of modern drug use in the post-war west is seen as “accidental” rather than central to many positive elements of our modern culture, I fear not only our we missing a huge opportunity to learn from this anthropologically, but also denigrating an activity which can be given greater freedom, rather than keeping it in a shady underworld which has its own elitism and privilege and denies a great many people both a greater degree of safety and potential to grow and learn and to become better versions of themselves.